- Home

- Buckley, Fiona

Queen of Ambition Page 6

Queen of Ambition Read online

Page 6

I opened my mouth to ask what was on offer and then remembered that I was not here as Ursula Blanchard, court lady, but as Ursula Faldene, cousin to Roger Brockley. I had decided to use my maiden name, in case Jester should happen to mention me to his half brother, and in case Giles Woodforde had heard my name at Richmond. I subsided and looked at Brockley, silently asking him to do the talking instead.

Brockley, therefore, inquired what was to be had. “We’ve got chicken and onion pasties,” said Ambrosia. “Or chicken pies without onion. The chicken was fresh-killed today. We don’t hang poultry in summer. We’ve got some of the mutton pie from yesterday left as well, and that’s all right, too. Or there’s bread and cheese, and radishes. With small ale or milk to drink.”

She rattled it all off efficiently, in an accent a little more educated than the man’s, but she sounded as though she had said it at least a hundred times that day and would probably be reciting it that night in her sleep. We settled for chicken pies, Brockley and Dale with onion and myself without, and small ale to go with it. Brockley gave her his best and pleasantest smile, and as though we had heard nothing of the quarrel, asked if she had worked there long.

“All my life. I’m Master Jester’s daughter,” she said, and whisked away.

“What an odd-looking girl,” whispered Dale.

“Yes, very unusual,” I agreed. She had been facing the light from the open front of the shop and I had seen her features as well as her hands and eyes. Ambrosia Jester had the kind of face that is ugly or attractive according to your personal taste. It was slightly squashed from brow to chin, as though someone had put her chin on a tabletop and then placed a heavy weight on top of her head. Her lips were a fraction too thick, her nostrils a fraction too splayed, and her dark eyes were deep-set under brows that swept dramatically upward at the outer corners.

Yet it was a face with character and even passion, and judging from her father’s strictures, she had found a focus for that passion. She was no clod—and her indignant parent, whatever Cecil might say about his style as a correspondent, hadn’t sounded like a bore. That word didn’t fit Master Jester, any more than it fitted Giles Woodforde, whose impassioned outburst I had witnessed in the corridor at Richmond.

“This family,” I remarked, “begins to look interesting.”

“You mean to go through with this?” Brockley asked me.

“I think I must. We’re not going to find out very much just by sitting here and eating their pies. I’ve got to get right inside the place.”

“Are you sure, madam? After all, I understand the scheme was started by the students and has been taken up by this man Giles Woodforde, who is inside the university.”

“But it will involve this shop,” I said. “I’m leaving Woodforde and the students to Henderson, because he can roam round the university more easily than I can. But the shop must be investigated, too. I’m going to try.”

Our food and drink arrived, brought this time by a different girl, a skinny young one with timid blue eyes and pale hair trailing like wisps of straw from under her cap, and we stopped talking until she had gone. Then I said: “I can’t think of any other way of finding out anything at all! I know you won’t be far away.”

“I certainly will not!” said Brockley. “I wish, madam, that you wouldn’t rush into these things so eagerly. You always say that you will be all right, that you won’t court danger, but …”

“I know, Brockley. I’m sorry.”

I smiled at him, my dear, reliable Brockley, with his gold-freckled skin and his level gray-blue eyes. Like his wife, Fran, he was in his late forties, and his wiry brown hair was now receding fast and streaked with gray. But he was, as ever, reassuringly solid in build and his calm voice with its trace of country accent never changed. The hands that were now breaking up his pie were the strong, steady hands of a horseman. Before entering my employment, he had been a groom and in the past, for a time, he had been a soldier. He smiled back at me and I saw Dale glance quickly from him to me and then look down at her food, and secretly, I sighed.

Brockley and I were not just employer and servant; we were also friends and colleagues. Once, during a terrifying night we had spent shut in the same dungeon, we had come perilously close to becoming lovers. We had not yielded, but nevertheless, somehow or other, Dale was aware of the attraction between us. Just as Mattie Henderson was aware that for all his charm and good looks, I had no desire for Rob Henderson, nor he for me.

That awareness was why I had made such a point of explaining to Fran that when Brockley and I talked so earnestly as we rode toward Cambridge, we had only been discussing plans about the pie shop, and it was also the reason why she had been so sour about Rob Henderson going off to Cambridge and leaving his wife behind. She had been saying to me, in cipher as it were: I feel that there is something between you and Roger that leaves me out in the cold.

I said: “It’s a great relief to me that you will both be at hand. That is, assuming that we manage to arrange what we’ve come to arrange. Brockley … ?”

Brockley rose and went to the kitchen door. He called, and the girl Ambrosia appeared again, this time with a floury rolling pin in her hand. Brockley spoke to her quietly. She glanced quickly past him to look at me, and then disappeared into the back regions. Brockley returned to our table and a few moments later, a man came out into the shop. I saw at once that he could very well be related to Giles Woodforde. He was bigger, but he had the same oddly nondescript air about him. Five minutes after parting from him, you would be hard put to it to remember the color of his eyes or the shape of his face.

“This is the owner of the shop,” Brockley said to me, not quite in his usual respectful tones. “His name is Master Jester. Master Jester, this is my cousin, Mistress Ursula Faldene. She is in need of respectable employment …”

6

The Pie Shop in Jackman’s Lane

Life in Jester’s Pie Shop was hell.

It was nearly as bad, I thought bitterly, as I crawled out of bed at half past four after my third night there, as life at Faldene House had been, when I lived there on sufferance with Uncle Herbert and Aunt Tabitha, never knowing from one moment to the next when my aunt or uncle would decide I had said something impertinent or failed to perform a task quickly or adequately enough, with painful results. Looking back, I wonder now if I encouraged, not to say seduced, Gerald Blanchard, my cousin Mary’s betrothed, because he was a way of escape.

On the face of it, of course, I could have walked out of the pie shop at will, since I was there under false pretenses. Brockley had told Jester that he and his wife, Fran, were taking service in Cambridge, but that he wished to look after his widowed cousin Ursula and had, therefore, brought her to Cambridge as well and was seeking a good live-in post for her. It had occurred to him, said Brockley, exuding flattery, that Cambridge was about to become very busy and perhaps such a flourishing business as the pie shop might want an extra hand. Oh yes, his cousin Ursula could cook!

Fortunately, this was true though I had come to it comparatively late. I didn’t learn much about cooking at Faldene, because while my mother still lived she had resolutely defended me from my aunt’s attempts to turn me into a kitchen maid, and made sure I was educated. Later, Uncle Herbert found my education useful, since he could make me into an unpaid clerk, to keep his accounts. But I had picked up a good deal of culinary lore once I was married to Gerald and again when I became mistress of Blanchepierre. I could act the part required.

And act it I must. The freedom to walk out was a privilege I could not use. I was here for a purpose and to achieve it, I had to put up with whatever the pie shop demanded of me and whatever Master Jester chose to throw at me: accusations of impertinence, wooden platters, or blows. In referring to him as a baa-lamb in comparison to my uncle, I had been horribly wrong. Jester and Uncle Herbert were kindred spirits.

Above the pie shop, I shared not only a room but also a bed with Ambrosia and the thin maidservant P

hoebe. We rose at half past four, washed faces and hands in cold water, scrambled into our clothes (mine were all commandeered from Dale), and sped down to the kitchen to break our fast with whatever rolls were left over from the day before, smeared with dripping and washed down with small ale, swallowing it all as best we could while simultaneously starting the bread oven, rousing up the fire, and putting the giant stockpot on to heat.

Then Phoebe would uncover the basins of dough that had been made the night before for today’s bread and pastry, and start shaping and rolling. I, however, had been given a different job. Jester, who to be fair to him was always down before time, and Wat, the pink-faced lout who manned the street counter, and slept beside the fuel store on the ground floor, would soon be busy killing the day’s supply of poultry. Master Jester, it appeared, set great store by the excellence of his ingredients. He had many regular customers, including some who did not come to the shop but had pies delivered to them, and he intended, he said, to keep their goodwill. He bought only a limited amount of meat from butchers, especially during the summer months. There was a fenced run in the back garden where he kept a dozen ducks and hens for eggs, along with the birds that were regularly bought live on market days and slaughtered as required. As Ambrosia had told us, during the summer he did not even let the birds hang.

Jester bought what he could get—capons, ducks, geese, or wildfowl brought in by fowlers from the fens—and mixed the meats if need be. I had to help Wat pluck and draw the birds and cut them up for the pot. “He never gets ’em done quick enough. Needs another pair of hands,” Jester had told me. “I was thinkin’ to get someone else, with the extra custom there’ll be while the queen’s in the city. Ambrosia’s got the fowls to feed and the eggs to collect and the sawdust to spread and I’ve got the marketing to do. You’ve come as a bit of luck.”

When Wat and I had finished, the pieces went into a cauldron with some ladlefuls of stock, to be stewed slowly till they were tender. Then the meat could be stripped from the bone, cut small, and mixed with mushrooms, oatmeal, onions, and spices to make pie fillings. When Jester did buy from butchers, he usually purchased sheep or pig carcasses, and these were similarly prepared. He never bought beef. It was twice the price of mutton and, therefore, too expensive.

We had to toil hard but it could have been companionable if we could have worked together in a friendly fashion. Alas, instead of amiable cooperation, we had Roland Jester continually finding fault in the shrill, aggrieved voice that went so ill with his big physique.

“Phoebe, what’re you doin’ with that dough? Get the loaves into the oven for the love of God; we’ll have the customers poundin’ at the shutters afore long. Hurry up, girl, or I’ll be after you with a stick, I will. Ambrosia, take that basket of eggs to the pantry afore someone knocks ’em clean off the shelf! Ain’t them fowl drawn yet? What are they—freaks? They got twice as much inside ’em as ordinary fowl? You’ve not got time to stand still and eat, Wat. Leave off guzzlin’ that roll and get busy with the cleaver … and don’t answer me back, you great loon; I’ll give you I’m working as fast as I can, Master Jester!” And with that, Roland Jester’s callused palm would crack against the back of Wat’s head.

The most frequent victim was Wat, because he was the only one who deliberately answered back. Wat himself paid these onslaughts little heed, because he was so hefty that he merely shook his head when Jester’s palm landed, as though to discourage a bluebottle.

For all his loutish appearance, though, Wat had a chivalrous streak. Once or twice, Jester had hit him for stepping in the way with a disapproving, broad Norfolk: “Aisy naow, aisy!” when the real target was Phoebe. Phoebe, who could be no more than fourteen, was too timid to do any answering back, but she was sometimes awkward and often drew Jester’s ire by dropping things or clattering them.

Wat seemed shy of me and so far I hadn’t had anything like a conversation with him; indeed, because his accent was so broad, I found it hard to understand him. All the same, he had twice come wordlessly to help me haul the insides out of a difficult bird.

However, he wasn’t always there to interfere on Phoebe’s behalf and as yet hadn’t actually tried to defend me from Jester, though I would have been grateful if he had. I was deft enough and I tried to be respectful, but I seemed to have a positive knack of inadvertently saying things that Jester considered impertinent. Phoebe and I were both liable at times to find ourselves ducking a hurled platter or seeing stars as Jester’s powerful palm sent one or the other of us reeling across the kitchen.

He didn’t, I noticed, hit Ambrosia or throw things at her. When one morning her father actually knocked me flat on the kitchen floor, Ambrosia picked me up and since Jester had by then marched out of the room, she explained, in apologetic tones, why she was exempt.

“I have to give orders when he’s not here and he thinks I’ll be respected more if the rest of you don’t see him knocking me about, so most of the time he doesn’t—though it happens now and again. He used to treat my mother very badly, though. I hope you’re not much hurt. Sit here for a moment.”

She helped me to a stool. A wave of her heavy dark brown hair slid free of her headdress as she did so. Ambrosia had beautiful hair, although no one ever saw much of it because her father made her wear very concealing caps. I opened my mouth to ask her how long it was since her mother left, but my throbbing head managed, just in time, to remind me that I wasn’t supposed to know anything about the household. Instead, I said: “Is your mother dead? How old were you when you lost her?”

“She isn’t dead,” said Ambrosia. “She ran away five years ago. I miss her but I don’t blame her for going. My father cried after she went—sat and sobbed, if you can believe it—but he’d made her life a misery and that’s a fact.”

Roland Jester certainly made his servants’ lives a misery. It was no better once we started serving customers. We were hurried and harried every moment, constantly urged to produce pies more quickly, although it was a mystery to me how we were supposed to make the oven bake pastry faster. The time that Jester knocked me down, it was for saying so. I was too used to speaking my mind, I suppose, and couldn’t get out of the habit.

Time and again—because the simple fact that I was not really Master Jester’s helpless employee meant that his blows made me more furious than frightened—I yearned to storm out of that hateful shop and send Roger Brockley or Rob Henderson (or better still, both of them together) around to have a few words with its proprietor. I had fantasies of the two of them putting him in bed for a week. Meanwhile, I strove to suppress my fury and endure. The days were passing and what, so far, had I found out? I had tried my best and until now I had achieved next to nothing.

My efforts in the last three days had included trying to eavesdrop when Master Jester talked to anyone—his daughter, his customers, or his neighbors. We had no neighbor on the Silver Street side of the pie shop, of course, but the adjoining house on the other side was occupied by a Master Brady, a bronzesmith who had separate business premises elsewhere, and his wife and family. So far, this had revealed such breathless secrets as the fact that the weather was very warm, that the prospects for the wheat harvest were good, and that students were an unruly breed.

I had also tried to pump Master Jester by asking artless questions. When he bothered to answer me, which wasn’t always, his replies were just as unhelpful. Yes, of course, he was looking forward to the royal visit. He was a loyal subject of the queen and hoped that her presence in Cambridge would bring in business. It was an honor for the shop to be involved in this playlet that the students and his half brother had concocted. A blank sheet of paper would have told me more.

Rob Henderson had furnished me with the names of the students involved in the playlet. So far, they had come to the pie shop only once. This was a lively occasion because they broke off in the middle of their meal to rehearse the sword fight for the playlet, with one of them pretending to be Dudley. They did it in slow, stylized f

ashion, but I had with some amusement watched Master Jester snatching tankards off tables, out of the way of the sticks they were using instead of actual swords, and listened while a young man called Thomas Shawe, who had an engaging grin and an extraordinary head of hair, which was neither fair nor red but was the color of slightly dulled brass, kept insisting that the boy who was taking Dudley’s part must turn this way, not that, “or the public won’t see properly and Master Woodforde says we’ve to give a proper show.”

I understood that Dudley had been told of the moves and would have studied them in advance and that when he reached Cambridge, there would be a further rehearsal with him but probably only one, for lack of time. I wondered if the Master of the Queen’s Horse realized how very amateurish the whole affair was going to be.

I had also gathered from Ambrosia that Shawe was the Thomas she was in love with, and that he was the one who had actually thought of the original rag. She told me about him by way of explaining why her father wouldn’t let her serve at the tables when he was in the shop.

“We want to marry but Father was so angry when he found out. He won’t hear of it. Maybe you overheard him shouting at me about it the time you first came into the shop.”

“I did hear something, yes,” I admitted.

“And it’s not just that I’m trade and Thomas isn’t,” she said resentfully. “Father just doesn’t want to lose me. I work hard and he doesn’t have to pay me. He’ll stop me marrying at all if he can.”

“Oh, my dear!” I said, suddenly very sorry for her indeed, and conscious that I was at least ten years older than she was and had had two husbands. I felt I ought to be able to advise her, but couldn’t think how.

Unexpectedly, however, she said: “I understand him, in a way. We’re not hard up—far from it—but he was poor as a boy and he’ll be tight with money all his life. And he’s not good at … at”—she frowned, as though she had never sought words for this before and was finding it difficult—“at impressing people, making them do what he wants, so he shouts and hits out. I sometimes feel I ought to stay with him to look after him. He’s my father, after all.” She saw the sympathy in my face and added: “When I was younger, Uncle Giles—he’s my father’s half brother; he teaches at the university nowadays—urged Father to get a tutor for me so that I could be educated, and Father agreed, though I think my uncle helped with the fees. I had a good tutor, too. Dr. Barley, his name was. He taught me Latin, though with Greek I never got much further than the alphabet …”

The Siren Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's

The Siren Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's The Doublet Affair (Ursula Blanchard Mysteries)

The Doublet Affair (Ursula Blanchard Mysteries) Queen of Ambition

Queen of Ambition A Pawn for a Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's (Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court)

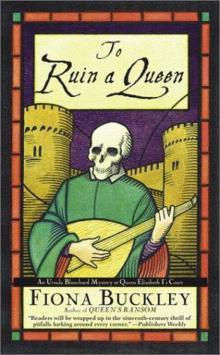

A Pawn for a Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's (Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court) To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court

To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court