- Home

- Buckley, Fiona

Queen of Ambition Page 2

Queen of Ambition Read online

Page 2

Yet Withysham was not truly my home. Home was the French château of Blanchepierre in the Loire Valley, where my second husband, Matthew de la Roche, was living. During a visit I had made to England earlier in the year, plague had broken out at Blanchepierre and Matthew had written bidding me stay where I was until the summer ended. The plague always subsided when the weather cooled. Making the best of it, I decided to pass the time putting my new property at Withysham to rights, before joining the court and accompanying the queen on her Summer Progress. I had once been a Lady of Queen Elizabeth’s Presence Chamber and during my stay in England I had found that in her eyes, I still was.

On that June morning, I had begun as usual by taking Meg with me to the kitchen to listen while I gave the orders for the day’s meals. While we were there, our spit boy, who was sharpening knives, cut himself and Meg helped me to dress the wound, using an ointment prepared from herbs by Gladys Morgan, an aged woman from South Wales. Gladys had attached herself to me in a way that was often an embarrassment, for she was, to be candid, a dreadful old woman. I could insist that she washed and wore respectable clothes, but her few remaining teeth still resembled fangs and her laughter was a demonic cackle.

Roger Brockley, who had a kindness for the aged, had once rescued her from a charge of witchcraft and now I lived in dread that one day someone would bring the charge again. True, the Withysham people didn’t dislike her as her former village had done. She had a gift for brewing medicines and ointments and had helped quite a few of them with her lotions for rheumatism and her potions for fevers. The old steward suffered from breathlessness and palpitations, and for him she had made a concoction of foxglove that had relieved him a good deal. I had cause to be grateful to her myself, for she had once saved the life of my woman, Fran Dale, and she had lately invented a brew that eased my occasional attacks of sick headaches better than the chamomile infusion I had used before.

She had, however, irritated the local physician quite a lot by her ministrations and I had had to be firm with both of them, telling Gladys to be more discreet and recommending the physician to mind his own business, attend the patients who called him in, and leave the rest alone (I felt no compunction about this; I was fairly sure that he killed as many as he cured and Gladys was better than he was about warning people of the difference between a healing dose and an overdose).

Gladys, in fact, was useful, but she was also a responsibility. After attending to the spit boy, I seized the chance of explaining all this to Meg, for I hoped that one day my daughter would marry well and have her own home and then she too would have to keep the peace among her servants.

Having finished with the kitchen, I had time for more intellectual pursuits. Meg and I were reading books of history and travel together, and I had bought a Latin grammar so that we could work on Latin, in which she already had a grounding.

It was an excellent mental exercise for me, too. I had lately become aware of how miserable women could be when their beauty began to fade, unless they had other interests. I had also discovered that such studies could be a defense against the languorous persuasions of summer weather, the scent of roses, the sound of grasshoppers, the voices of dove and cuckoo, and the eventide song of the blackbird. When I was concentrating on a Latin translation, I did not daydream about Matthew.

At court, I had often been impressed by Queen Elizabeth’s own interest in learning and her gift for languages. Sometimes I wondered whether Elizabeth, determinedly unmarried and still only thirty, also found her intellectual pursuits a refuge from importunate desires.

I did not intend to give up my own studies once we were settled back in France, however. On the contrary, I hoped to find a tutor who could instruct both Meg and myself not only in advanced Latin but also in Greek. My education had been a matter of sharing my cousins’ tutor, and although we had gone a fair way with Latin, my cousins had pleaded to give up Greek almost as soon as they began it, on the grounds that it was too difficult. We had learned the alphabet and not much else.

For the moment, though, Meg was only at the stage of basic Latin and that was occupation enough for us. I settled down with her in the small room that I had chosen as a study, which looked out toward Withysham’s neatly thatched gatehouse, and to the home farm fields on the hillside beyond our encircling wall.

As she often did, my woman, Fran Dale—I still called her Dale although she was actually Mistress Brockley—joined us, to sit by the windows with some mending. Because the day was warm, two of the casements were open, letting in the sound of skylarks and the smell of new-mown hay from the fields. Meg sat with her head bent earnestly over an exercise concerned with the fourth declension, while I tried to puzzle out a grammatical point that had always confused me, involving the construction of the gerund. Though I remember, on that morning, I wasn’t concentrating as earnestly as Meg. There were occasions when intellectual tasks didn’t quite succeed in blocking out emotional ones. I kept on raising my head to look with affection at my daughter, who was becoming so very pretty.

She took after her father, Gerald, who had been a handsome man. Her glossy hair was dark just as his had been, and she had his brown eyes. I had dark hair too, but not quite of the same shade, and my eyes were hazel. I had dressed her in a lightweight crimson brocade, which suited her to perfection, and her little white linen cap was clean on that morning. Sitting there so studiously, she was such an enchanting picture that she distracted me from my books and from the sights and sounds of the outside world alike. I did not want to stop looking at her.

And I was realizing that despite the empty place beside me, which must always be there until I was reunited with my present husband, Matthew, here at Withysham in the company of my daughter, living this quiet life of domestic duties and peaceful study, I was surprisingly content.

It was Fran Dale who heard the distant clatter of hooves on the gatehouse cobbles, looked out of the window, and exclaimed: “Mistress Blanchard, ma’am, there’s a royal messenger just ridden in, or my name isn’t Dale.”

“Well, it isn’t, is it? It’s Brockley!” said Meg with a giggle.

“Meg, don’t be pert,” I said absently. “Dale is sometimes known as Dale and sometimes as Mistress Brockley. In France, when we go there, I shall be Madame de la Roche, but in England I prefer still to be Mistress Blanchard. People aren’t always called by the same name all the time.” I rose and went to the window. The horseman was walking his mount toward the stableyard and he was near enough for me to see from his livery that Fran was right.

Well, I was expecting him. This was my summons to join the queen and prepare for the Progress to Cambridge. But it had come well before I looked for it, and I not only wished it hadn’t, because it felt like an intrusion, I also wondered why it had come so soon.

It was my first intimation that something out of the ordinary was afoot.

When the time came for me to go to France, I intended to leave Brockley and Dale to run Withysham for me. I would have plenty of servants at Blanchepierre. But in England, I only had Brockley and Dale as personal attendants, so they would have to come to Cambridge with me. Therefore, I recalled the old steward, Malton, from his retirement cottage and put him back in charge with a lengthy list of instructions, which included taking the utmost care of Gladys. “I won’t be here and Brockley won’t be here, but if anyone harms Gladys while we’re gone, you’ll answer for it. I’ll slash your pension.”

“I’ll do my best, Mistress Blanchard,” said Malton bleakly. He had never known what to make of me but he was more than a little afraid of me, which just now was all to the good.

“You’ll do more than your best,” I said. “Call on the vicar for help if necessary.” The vicar’s living was in the gift of Withysham and he was afraid of me, too. I was young to be a husbandless lady of the manor and sometimes I had to put on fierce airs in order to get my authority respected. I sometimes feared that I was turning into a fair facsimile of a battle-ax.

Meg, alo

ng with her nurse, Bridget, would have to return to her foster mother, Mattie Henderson. Rob and Mattie were the owners of a big house near Hampton and Rob was a courtier, and a friend of Sir William Cecil, the Secretary of State. Rob was to join the Progress and Mattie had written to me that he was already at court. Mattie herself, however, was expecting a child and was to stay behind at their home, Thames-bank. Meg was well used to both Mattie and Thames-bank and would be contented enough there until I came back.

“Though I don’t envy Mistress Henderson, having to stay at home while her husband goes off gallivanting among all the court ladies,” Fran Dale said in sour tones. “And her nearly forty, at that. If I was her, I couldn’t abide to see Roger going off like that and leaving me behind.”

“No one’s asking you to,” I pointed out, somewhat brusquely, since I was extremely busy just then with the choice of gowns to pack and a further list of last-minute instructions for the harassed Master Malton.

The day before I set out, I had an unexpected visitor. Five miles from Withysham was Faldene, the house where I had been brought up, mainly by my uncle Herbert and my aunt Tabitha. My mother had been a court lady who was sent home in disgrace, with child by a man she would not name. I had been that child. Her parents and later on her brother Herbert and sister-in-law Tabitha had sheltered us, had clothed and fed us, and had even educated me, but they had not been kind. We had disgraced them, and they let us know it.

Later on, when my mother was dead and I was a young woman confronted with a life as Aunt Tabitha’s unpaid maidservant and Uncle Herbert’s unpaid clerk, I succeeded in stealing the affections of their daughter Mary’s betrothed. I ran off with Gerald and married him. Finally, when Uncle Herbert became involved in treason, I was the one who got him sent to the Tower. He had been released long since, as an act of mercy, because he was a heavily built man who suffered from shortness of breath and attacks of gout, but understandably, he didn’t feel inclined to forgive me.

In fact, for excellent reasons, I didn’t like my uncle and aunt and they didn’t like me and although I lived so near them, we had not seen each other during my sojourn at Withysham. I was very surprised when Brockley came to my chamber, where Dale and I were folding clothes into hampers, and announced that Mistress Tabitha Faldene was below, and wished to speak to me.

“Aunt Tabitha? Here?”

“Yes, madam.” Brockley knew the situation and his calm high forehead with its dusting of pale gold freckles was faintly wrinkled with surprise. “I have asked her to wait in the main hall.”

I went downstairs and there, indeed, she was, thin, vinegary Aunt Tabitha, neat and prim in a stiff, narrow ruff, her housewifely dress of dark blue tidily draped over a modest farthingale. Aunt Tabitha did not care for showy garments.

“So there you are, Ursula. I won’t ask you why you haven’t called on us. Tact, no doubt, and in fact, you were right. Your uncle does not wish to see you and of course I respect his views. All the same, families should maintain the proprieties. I hear you are bound for the court again and I felt it was only proper that I should speak with you before you left. If you wish to visit your mother’s grave in Faldene churchyard, you may do so.”

“Thank you, Aunt Tabitha,” I said in astonishment. Tabitha was a stickler for the proprieties she had mentioned, but I hadn’t expected her to maintain them after what I had done to Uncle Herbert. I did indeed want to visit my mother’s grave, and had been planning to go there very early one morning and do so before people were about. I didn’t bother to ask how my aunt knew I was going to Richmond. Half the Withysham villagers at least had relatives in the village at Faldene.

I called for refreshments and asked after my uncle and cousins. My uncle’s gout had been better of late; my cousins, all now married, were apparently thriving. My cousin Edward was actually married to a distant relative of Gerald’s and now had a baby daughter.

“We were pleased,” Aunt Tabitha said, “when we heard that you had settled in France with Matthew de la Roche. We hoped you had seen sense at last and perhaps your husband would save your soul for you. We were also pleased, though surprised, to hear that Withysham had been restored to the two of you. But are you going back to France?”

“Yes, in the autumn. I shall take Meg with me.”

“And in between, you are returning to court and the service of that red-haired heretic of a queen. It seems that you can hardly keep away from her.” Aunt Tabitha and Uncle Herbert adhered to the old religion, which was how they had got entangled in treason.

I looked at her coldly. There had been an occasion, long ago now, in the days of the passionately Catholic Queen Mary, when she and Uncle Herbert had returned from witnessing a burning, and by way of warning me against heresy, had forced me to listen while they described it. I still had occasional nightmares about that. I would never either forget it or forgive it. “The days of the heresy hunts are over,” I told her. “And people are grateful to Elizabeth for it.”

“They may think differently when they reach the hereafter.”

“I was sorry for Uncle Herbert, believe it or not,” I said. “And I do have a sense of family loyalty. But—I have other loyalties, too.”

“That is obvious,” said Aunt Tabitha, and unexpectedly sighed. “Ah, well, I suppose we must be glad that at least you mean to return to your husband. Your first loyalty should be with him, after all.”

We exchanged a few more desultory words and then she took her leave, repeating that I was welcome to visit my mother’s grave though I should not come to the house. The whole visit had a very odd atmosphere. My aunt’s attitude had been—well, not quite conciliatory but close to it—and she had been strangely lukewarm about the news that I was going back to France in the autumn. It was almost as though she didn’t want me to go. I felt as if she had come for some purpose that she had not declared.

But I had no chance to pursue the matter. I did visit my mother’s grave, very quietly, early the next day. And then it was time to load the pack ponies, mount our horses, and go. The court was beckoning.

And it really was beckoning. It was always the way. Once I had done with saying good-bye to Withysham and dried my tears on parting from Meg, my resentment and surprise at this early summons faded away. The prospect of the court, the exhilaration of it, the cut and thrust and double-talk of political maneuvers, and above all, the personality of Queen Elizabeth, glittering, dangerous, vulnerable, frightening, and lovable, began to seduce me. Elizabeth and her court were like a heady wine, and I was an addict who longed with all her heart to drink of it once more.

3

Nondescript and Importunate

I liked Richmond. With its ornamental turrets and sparkling fountains, and its well-lit, airy rooms, it was to my mind the prettiest of all Elizabeth’s residences and for me it had good associations. After Gerald’s death, when I was an impecunious young widow who was lucky to have friends who had found her a post at court, it was to Richmond that I had come, to enter a new life and it was there that my grief had begun, slowly, to heal.

It was there, in the summer, when the gardens were in bloom, that Matthew and I had first met.

This too was summer and as Dale and I, accompanied by a page and two men to carry our hampers, made our way toward the palace building, the sanded path led past flower beds ablaze with color. The air was full of the hum of bees and the beguiling perfume of lavender and roses.

A few gardeners were busy with weeding, and courtiers, men and women, their costly doublets and embroidered skirts as vivid as the flowers, were strolling along the paths. One or two of them recognized me and called greetings. I returned the greetings but did not stop. The June day, so beautiful when one was sauntering through a garden, had also meant a hot and dusty ride from Thamesbank, where I had left Meg in the morning. Even the horses had been weary at the end of it. Brockley had taken them off to the stable, murmuring soothingly to them about buckets of water and fresh hay. Being used to riding, I was not unduly tir

ed but I did feel the heat and Dale was drooping badly. She was in her late forties and she had never liked horseback travel. She had already said that she hoped the Progress to Cambridge would be the last long ride she ever undertook in her life. The sooner we were in a shady room, washing our faces in cool water, the better.

Once indoors, the page led us along a wide, flat-ceilinged corridor that turned a corner into an unfamiliar wing. Through the windows on one side, I saw sunlight flashing on the Thames, but I could not work out quite where I was. “I’ve never been lodged on this side of the palace before,” I said to the page.

He glanced at me, sidelong. He was about sixteen, exquisite in white and silver brocade, and with a nascent beard around his lips. Pages, in my experience, fell into four broad categories: the cheeky, the timid, the circumspect, and the knowing. This one was on the cusp between circumspect and knowing. “There are a number of guests at court, Mistress Blanchard, and Lady Margaret Lennox is among them. As is her custom, she has brought a large retinue and they need a great deal of accommodation. I have myself had to move into different quarters.”

I quelled a smile. His voice was almost completely bland, but there was the very tiniest trace of resentment in had to move. His new quarters were probably squashed and he would of course know all the court gossip about Lady Lennox. She was a cousin of the queen, since both of them were descended from Henry VII, and family propriety (Aunt Tabitha would have understood) required her to be treated with dignity. Elizabeth, though, had good reason to detest her, and did. Good courtiers followed Elizabeth’s lead and detested her too, and young pages, when they mentioned Margaret Lennox, could afford to let their voices be tinged, just, with dislike.

Though wise court ladies did not encourage this. I didn’t answer and was glad of that when, half a second later, a door on our left was flung open and through it strode Lady Lennox herself, no less, tall and commanding, her farthingale almost filling the doorway, her cream satin skirts adorned with enough embroidered flowers and sewn-on pearls to rival anything in Elizabeth’s own wardrobe, and one beringed hand angrily straightening a pearl-edged headdress, which seemed to be on the verge of toppling sideways off her waves of crimped brown hair.

The Siren Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's

The Siren Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's The Doublet Affair (Ursula Blanchard Mysteries)

The Doublet Affair (Ursula Blanchard Mysteries) Queen of Ambition

Queen of Ambition A Pawn for a Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's (Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court)

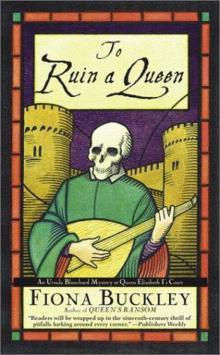

A Pawn for a Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's (Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court) To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court

To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court